Biking into the Future

Biking is on the rise in many global cities today. It used to be a very popular method of transportation but as cars started to become popular, bikes started to disappear. That was bound to happen as automobiles are a much more efficient way of transportation; They are faster, they can reach farther distances, they do not require any physical effort, they are weatherproof, they fit more people, and are overall a much more pleasant way to travel. It was obvious that cars were going to replace all other methods of transportation before it.

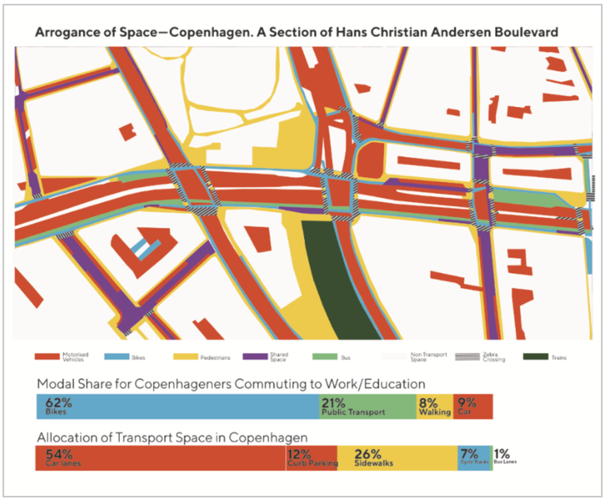

As the popularity of cars rose, the streets started to grow for them. This worked perfectly in the beginning. The problem came when cities started to grow to an extreme point. Currently, more than 50% of people live in urban areas and that number is expected to rise to 70% in 2050. Urban areas cover about 3% of the entire land area of the world. This means that more than half the population in the world resides in only 3% of the land. (Ritchie and Roser). At this rate, it is impossible to have streets wide enough to fit all citizens on cars. City planners have to start implementing new transportation methods and biking is one of the best options available. The following diagram shows a series of streets in Copenhagen. It shows how 62% of commuters on the streets were using bikes while only using 7% of the space of the streets and 21% were using public transportation while only using 1% of the space. In contrast, 9% of people commuted on cars while using 54% of the space. It is evident that cars do not fit on today’s cities.

Figure 1 Percent of Space in Transports. Photo: Colville-Andersen

Besides aiding in traffic, biking can bring “social, economic, and health benefits” to cities around the globe (Reid 8). This does not mean that all cities are apt for complex biking infrastructure. Planners have to use Jane Jacobs ideas and become “students of cities;” By examining how cities work, the planner can decide if biking is beneficial or not. It also takes more than just building bike lanes for people to actually start biking. Cities have to make biking a beneficial method to travel by having great lanes and by connecting them to public transportation.

Copenhagen

Copenhagen is the perfect city to analyze biking as a method of transportation. It is regarded by many as the “City of Cyclists” as the majority of its citizens use bicycles as their main way of transportation. In Copenhagen there is no bike culture, biking is just part of every citizen's culture. Copenhagen has been the world’s leading city on biking infrastructure for many years and its years of experience is the main reason why no other city can compare with it. Writer Carlton Reid explains on his book, Bike Boom, that “Copenhagen’s current high cycling modal-share is the result of more than 100 years of continuous improvements. Even at its worst in the 1970s, when cars started to overrun the city, Copenhagen had a cycling modal-share of 23 percent” (10).

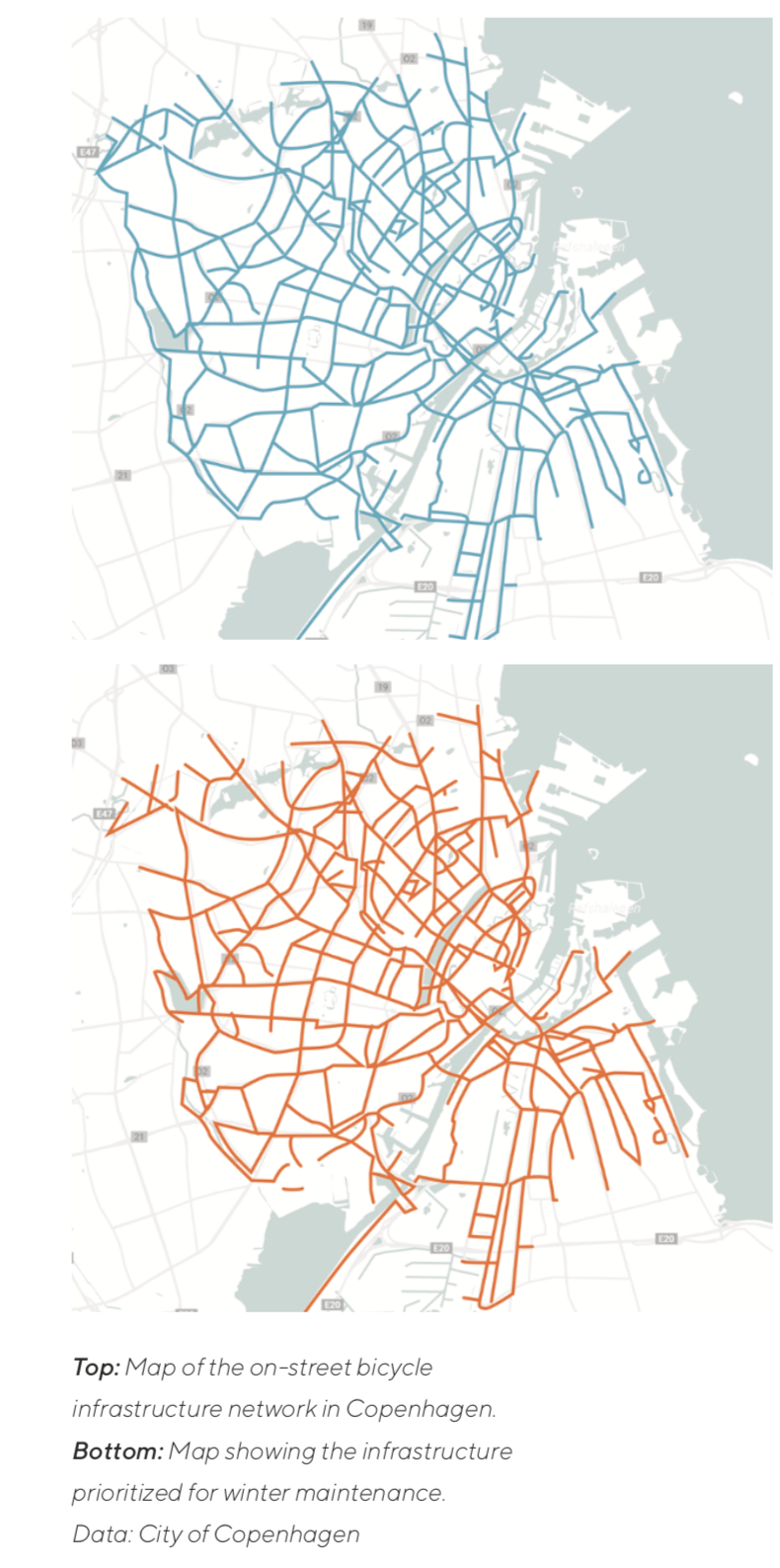

Biking has been a crucial part of the city’s urban planning forever but never as much as it is today. In Copenhagen today, “63% of the population commutes by bikes” (Colville-Andersen 203). This high percentage of cyclists is only because of the high number of bike lanes in the city. Mikael Colville-Andersen, in his book Copenhagenize, states that currently there are about 400 kilometers of bike lanes in the city (180). The maps below shows two things; first, it shows that most streets in Copenhagen have bike lanes and second, it shows that officials prioritize biking as all the lanes are taken care of during winter.

Figure 2 Map of Bike Lanes in Copenhagen. Photo: Colville-Andersen

This maintenance during winter leads to “seventy-five percent of Copenhageners [to] cycle all winter,” claims Colville-Anderson. The official policy is to have all the tacks to be “cleared of snow before 8:00 AM” (Colville-Anderson 25).

This prioritization of biking is why everyone bikes. Bike lanes in Copenhagen are not just small lanes painted in the roads beside the cars, they are protected highways only for bikes. Out of the 400 kilometers of bike tracks, “375 kilometers are curb-separated” (Colville-Anderson 180). This means that bikers have a barrier from the motorized traffic to increase safety and the traffic flow for both types of traffic. City planners in Copenhagen think about cyclists before all other methods of transportation. Protected bike lanes mean a much higher investment for cities, but it increases the number of cyclists on the track. This high number of protected lanes is not usual anywhere else.

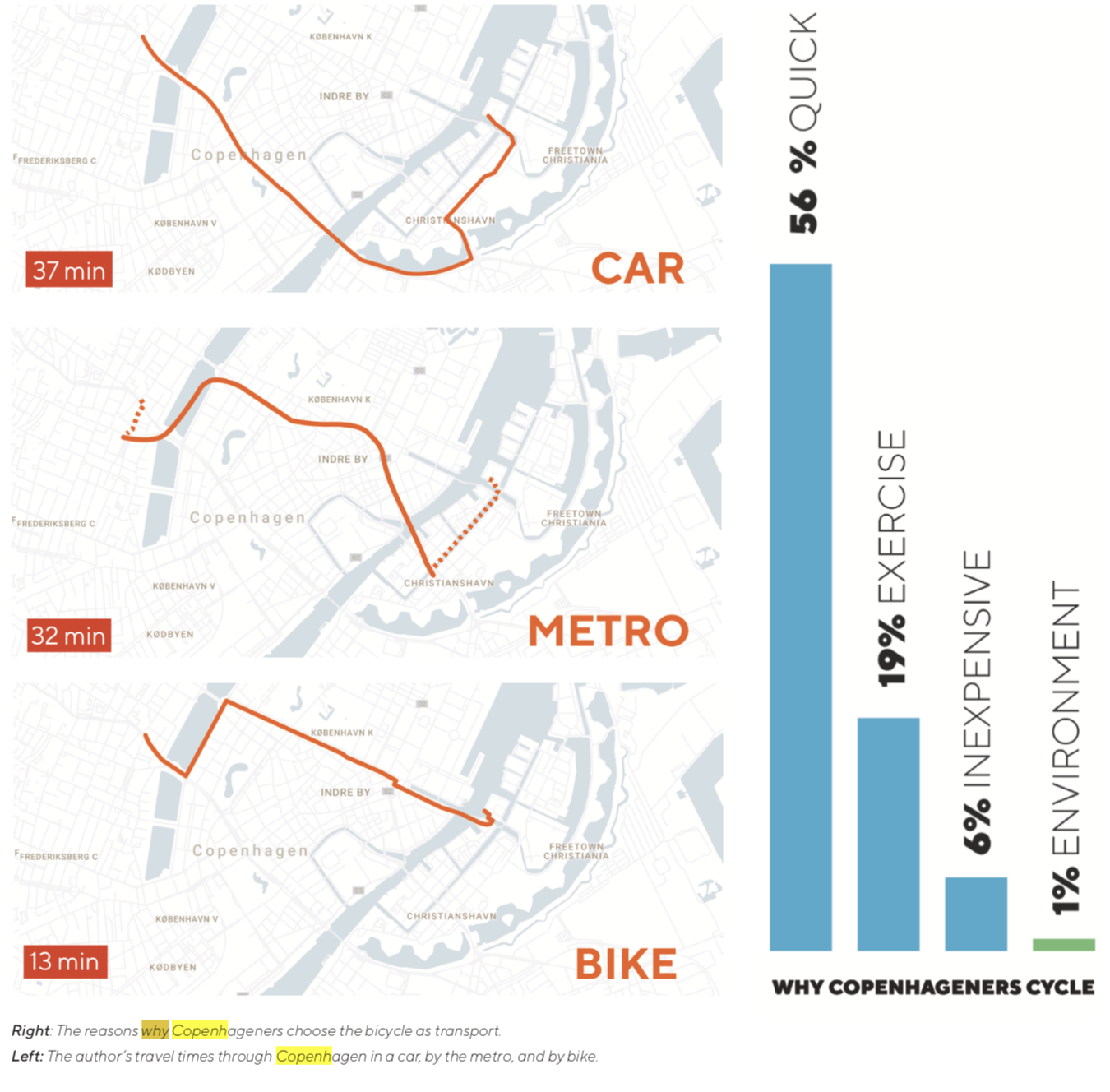

The citizens of Copenhagen are not “environmental warriors” for riding their bikes. Neither do they ride a bike to be healthier or to save money in gas (Colville-Anderson 131). They ride their bikes because the city has made it the best option. It is simply the fastest way to move.

Figure 3 Reasons for biking. Photo: Colville-Andersen

Copenhagen got all the benefits of a city cycling by almost forcing people to bike—they made biking impossible to resist. Currently, they are prioritizing biking as much as cities in 1970 where prioritizing cars. Copenhagen shows the world that building some bike lanes will not get people to bike. Building streets just for bikes and caring about the cyclists will get people to bike.

New York City

New York City has all the necessary characteristics for biking—it is extremely dense, distances are short, and the terrain is flat. That explains why cyclists have always existed in the city, however, the biking infrastructure has had a hard time coming to the city. Carlton Reid compares New York City’s cycling infrastructure to a “war” (216). A war, with important battles, between city officials and activists. One of the first battles happened between 1978 and 1987. It started after multiple demonstrations from activists that believed the city had to start implementing protected bike lanes for the growing number of cyclists in the city. At first, in 1978, the city’s Mayor, Ed Koch, believed the activists were right and that the city needed to start implementing a better cycling infrastructure to its citizens (Reid 211). The city started to pave new protected bike lanes throughout the whole city and it had positive impacts as “bike commuting tripled” (Reid 212). Even though the new lanes had positive results, it also had a massive opposition. Drivers hated the new lanes as “they were created by stealing space from parking lanes” and were believed to increase the already terrible traffic problem. After this criticism, Mayor Koch ordered the removal of all bike lanes that were built and even tried to “prohibit cycling on some streets altogether” (Reid 213). The ban was refused by the New York State Supreme Court, but cyclists lost the battle (Reid 214). The city refused to prioritize bikes and kept improving its streets only for the cars.

The war is far from over. Another battle is taking place in the City since 2007, and this time cyclists are winning. This battle was started by the former commissioner of the New York City Department of Transportation, Janette Sadik-Khan. The number of daily bike commuters in the city has had an impressive growth since 2005 and Sadik-Khan had an important role in it. When she realized that bike riding was increasing, she wanted to improve the bike lanes by introducing the first protected bike lanes since 1978. The city’s government decided to do a pilot for the protected lanes Sadik-Khan wanted to introduce. The pilot ran on “Ninth Avenue between 23rd Street and 16th Street in Manhattan” and became the “first on-street parking and signal protected bicycle facility in the United States” (Nacto). The Department of Transportation had been increasing the number of regular bike lanes in the city, but Sadik-Khan wanted them to be protected to increase the number of regular bikes. She believes that when women and children start using the lanes, it is evident that they are safe. The result of the pilot showed an increase in woman and children commuters and it showed an increase in retail in the passing stores. Sadik-Khan was extremely happy with the results and claimed that the pilot also lead to “crashes decreasing by 48%”, “retail sales increasing by 48%, all while keeping car traffic constant (Vox media). The pilot did remove the revenue from past parking spaces, as shown on the pictures below, but Sadik-Khan, with her department, showed the government losing parking space is worth it.

Figure 4 Pavement of Pilot. Photo: Russo, et al.

Figure 5 9th Avenue before Pilot. Photo: Russo, et al.

Figure 6 9th Avenue after Pilot. Photo: Russo, et al.

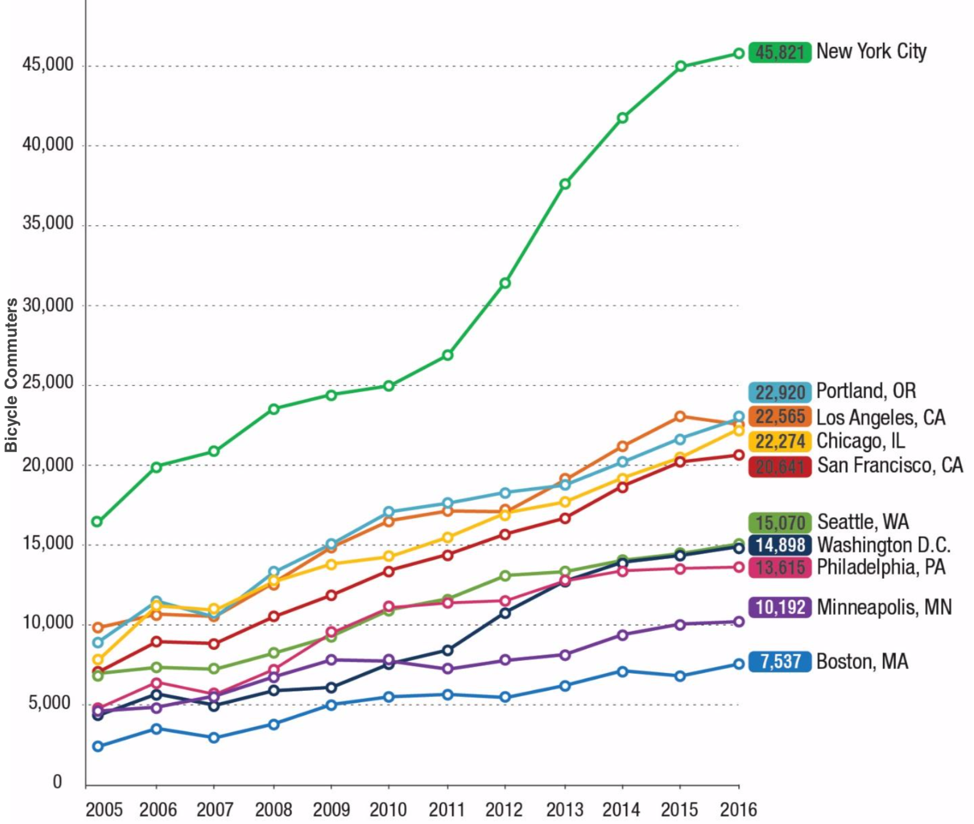

After this pilot success, the city has been implementing more protected bike lanes. Today, New York City has about 200 kilometers of protected bike lanes with a total of about 2,000 kilometers of lanes. This increase in biking infrastructure has expanded the number of daily bike commuters. A report from New York City’s government showed that the number of bike commuters has increased two times faster than any other city in the United States.

Figure 7 Bicycle Commuters Chart. Photo: "Cycling in the City”

Bike Sharing has also been an important factor in the rise of bike use in the city. Citi Bike started its operations in June 2013 and it has been steadily growing ever since. In its first report, on June 2013, it shows that the service started with “322 stations” to hold a fleet of “5,130 bikes”. On the first month, there was an “average of 20,619 trips per day” (June 2013 Report). Due to the growing bike lanes in the city, Citi Bike was able to start with great numbers and increase them every year. Comparing its first report to June’s 2018 report shows that growth. On June 2018, Citi Bike had “739 active stations” and a fleet of “10,494 bikes”. This resulted on an average of “65,098 rides per day” (June 2018 Report). By doubling the number of stations and bikes, it tripled the use. New Yorkers are also riding their bikes during the winter. Citi Bike’s report from January 2018, the coldest month of the year, shows that rides are not as common as in summertime, but it still has great numbers with an average of “23,193 rides per day” (January 2018 Report).

New York City has improved a lot in the past ten years and the same growth can also be seen in other large cities in America. However, Melody L. Hoffmann believes that this new bike infrastructure is not being created equal. In her book, Bike Lanes are White Lanes, she explains why bike lanes in the country have racist goals. She claims that city planners are focusing on high-class workers that are able to afford to live in the densest parts of town while forgetting the poor “invisible cyclist” that lives farther away in poorer communities (17). The title of the books is provocative, but it does not reflect entirely what she is trying to say; she is not claiming that planners are intentionally focusing on white riders, however, they are focusing their efforts on rich areas and not helping the poor neighborhoods. The reason that poor areas are mostly made up of African Americans and Latinos is not that of bike lanes, but rather the racism that has affected this country since the beginning. Hoffmann understands that bike lanes work better in rich, dense neighborhoods yet, she argues planners should help everyone. Planners should support new plans to help people that live in small apartment buildings “with no place to store bicycles” or help with the “fear of racial profiling or deportation” when driving (Hoffmann 25). The problem that Hoffmann brings is clear in New York City when examining where the bike lanes are put in place. The map of the city below shows how most bike lanes are placed in the richer parts of Manhattan. The green lines in the map are the protected lanes and it is clear that the priority is not in the poor neighborhoods of the city.

Figure 8 Map of Bike Track in NYC. Photo: New York City Government

New York City has definitely improved substantially on its biking infrastructure, but it still has a long way to go. For the first time, city officials are giving cycling a bigger priority when planning just like Copenhagen. Building bike lanes on every street do not mean that people will automatically start biking. Officials have to keep listening to the public to understand their needs and plan accordingly. If they continue to do this, cycling is going to continue growing and traffic is going to improve.

Guatemala City

The final case study of this paper is the about Guatemala’s bike infrastructure. Guatemala City, unlike Copenhagen and New York, is an extremely undeveloped city. It is the capital of Guatemala and the only real city in the country. The country of Guatemala is one of the poorest in the world, especially compared to Denmark and the United States. To understand how poor it is, the GDP per capita in Guatemala is of merely $4,471.00 while the GDP of Denmark and the United States is at $59,531.70 and $56,307.50 corresponding. Bike infrastructure is rarely seen in cities this poor. Today, one of Guatemala’s biggest problems is the traffic and they are starting to consider cycling as a possible solution. Guatemalans waste an average of three hours a day on traffic while the average worldwide is one hour and a half. Cars and motorcycles make up 94% of circulation on the city while public transportation makes up 2% and bicycles 0.14% (Morataya). The government wants to fix this problem and believes biking could help reduce cars and increase public transportation use.

The history of Guatemala City’s biking infrastructure, evidently, is much shorter than the other two cities discussed. The plan for the first bike route in Guatemala was put in place in 2009. The plan consisted of a protected bike lane of 4.7 kilometers near the campus of San Carlos University. It started construction in 2010 and had a projected cost of 18 million Quetzals or 2.3 million US dollars. The plan also consisted of 10 bike-sharing stations around the route with about 1,700 bikes for the students and other users of the route (Kont).

As is usual for any development in Guatemala, the project is having some delays. The first section of the bike route opened in 2011, and today it remains the only finished part of the project. This section consists of a 1.2-kilometer protected bike lane. It surrounds San Carlos University of Guatemala and connects it to the Aguilar Batres, one of the busiest streets in the country. The plan works in conjunction with public transportation as the bike lane leads directly to the closest bus stop from the university. Oscar Felipe Q, on his article for Prensa Libre, claims that the route is used 65 thousand times a month. This is a low number as using it is not worth it yet. Google Maps shows that 1.2-kilometer route as a 14-minute walk and a 4-minute bike ride. When the bike lane does grow, using a bike will have a much larger advantage than today. However, all this information does not mean that bikes are not being used by some people. In his article, Felipe Q interviews daily users of the bike tracks and they all seem incredibly grateful for the improvements to the infrastructure the city is making. The bike route even has the first two of the 10 planned bike sharing stations. The two stations have a total of 70 bikes for the use of the students, but it does get hard to get one during rush hour (Felipe Q).

Phase 2 of the project is in construction right now but there is no exact information on when it might be ready to be used—it was supposed to be ready by the end of 2018, but it has not been finished yet. This stage will add about 1.5 kilometers to the route in order to connect it with the Periférico, another important street in the city, and to the School of Medicine in San Carlos University. The phase also includes adding two more bike sharing station and more bikes for the estimated rise of cyclists on the route (Garcia). This addition to the route will surely attract more users to it as it will become a better option to bike.

The protected bike path of San Carlos University is the most developed and used bike track in the city but until recently it was the only one. From examining this bike lane and other cities biking infrastructure, the city’s government has started to realize the benefits that it could bring to Guatemala. To understand the government's realization, it is necessary to understand the current infrastructure in the city. Guatemala City is a relatively small area of 692 km2. It is divided into 22 zones expanding from Zone 1 which is where the Government is situated. As for most cities, the zones closest to the middle are much denser than the rest. This is perfect for a biking infrastructure to flourish. Furthermore, the dense areas are almost lined perfectly in a straight line that reaches Zone 1. Zone 1 is the most important zone, it is not only the house of the government, but it is also the financial center of the city. The busiest streets in Guatemala are straight streets that go from the residential areas and the airport, to zone 1. This is also the main route of the new public bus system, the Transmetro. The system follows a mostly straight path on a separated lane from other traffic. This can be better seen with the map below.

Figure 9 Google Maps of Guatemala. Photo: Carlos Cojab

All these factors mean that Guatemala City is a perfect candidate for the devolvement of bike infrastructure. As traffic becomes the worst problem in Guatemala, bike infrastructure could reduce drastically the number of cars in the streets. The government has realized this and has started developing a complex plan for new biking infrastructure. The plan started in 2011, after the construction of the bike lane in San Carlos University. The plan is to construct around 200 kilometers of bike lanes around the center of the city where the traffic is at its worst to connect people to the Transmetro lines. The map from BiCuidad bellow shows exactly that. The planned bike routes are in blue, and the green lines are the Transmetro lines. The black circle has a radius of 5 kilometers, it represents an estimated 20-minute bike ride anywhere starting from the orange dot in the middle.

Figure 10 Planned Bike Tracks. Photo: "Moviendo a Guate”

By living in Guatemala, I have been able to see the birth and slow growth of its biking infrastructure, but I have rarely seen cyclists. The previous map shows the planned lanes, but it does not show that lanes that have been constructed already. The map of the existing lanes looks completely different as it only has a handful of short lanes, disconnected from each other. It is not surprising not to see cyclists as the routes do not lead anywhere. Guatemala also faces the same problem as New York City when it comes to who is being served by these current lanes; Just as New York City, the current lanes are located only on the richest parts of the city. The difference is that, in Guatemala, the people that live in these areas, are the least likely to start using bikes as a method of transportation. Guatemala City is the 24th most dangerous city in the world with a homicide rate of 53.49 per 100,000 people (Dillinger). The country is also the 15thmost unequal country in the world (Beaubien). So, the people that can afford to live in these areas are extremely wealthier than the lower class and are too afraid to start biking, or even using public transportation, as a way to travel. Several of the citizens that live in those areas even drive around in bulletproof cars, why would they ever change that for a bike? The placement of these first routes is questionable. They are placed in the densest areas of the city where bikes could really be useful, but they are also on the richest areas where everyone is too afraid to use them.

I was able to interview one of the most important people working on the project to comprehend the government’s decision making. I got in contact with Guatemalan Architect Eddy Morataya and we spoke on the phone about Guatemala’s current and proposed biking infrastructure. Morataya is an Architect and Urban Planner currently working for Guatemala’s Municipality. He is currently the Urban Mobility Director for the city and is in charge of the transportation in the city alongside the Mayor. Morataya, with the help of others, is working on the growing bike infrastructure in Guatemala. The interview started by discussing where is Guatemala currently in terms of biking infrastructure. He stated that “there are about 17 kilometers of bike lanes in Guatemala today, of which 90% are protected lanes while 10% are regular bike lanes painted on the side of the street” (Morataya). I asked him for the reason behind the location of these first bike lanes. He answered me by explaining that most of the constructed lanes are located on the “corredor central,” which refers to the central axial streets that lead downtown. He agreed with me that the people that live near will never give up their cars for a bike, but he told me that all this development is merely the first step. “We needed to build these first lanes that run through the rich sections of the city because they also run on the most important streets in the country. These streets are traveled by the majority of citizens every single day. The upcoming phases of the projects will expand the routes to reach more areas, but these first protected lanes were a crucial starting point.” He acknowledges that today, only 0.14% of daily commuters travel with bikes but he expects that number to grow after phase two is over.

Phase two of the project, as Morataya explained, consists of two elements—the addition of new bike lanes and the introduction of a much better and well-organized bike sharing service. His team calculates that the phase will be completed by the end of 2019. They are planning to add about 25 kilometers of bike track too but most of it will not be protected. Morataya is convinced that real improvement will come from the bike sharing. The only bike-sharing stations on the city right now are the ones near San Carlos University, but they do not work like similar services in other cities. Currently, the bike-sharing service in Guatemala is made up of two small kiosks with an employee that personally gives the user the bike. Morataya’s team wants to completely ameliorate the service by launching modern, electronic bike stations. He said that, “they want to replicate the Citi Bike service from New York City on the functionality and the financing of the service.” At the beginning of next year, they will hold a competition to find a company that will finance the project. Morataya explained that “the winner company will pay for the 52 proposed stations and the first 1,000 bikes for them in exchange, the service will be named after the company exactly like it was done in New York City.” He understands that in order to be used by most, the service has to be cheap. They estimate that the annual pass will cost around 600 Quetzales which is around $75 or $0.25 per day.

Morataya is convinced that the introduction of this will be the turning point for Guatemala. He claims that by having this, people will start using the bike lanes as “they will always have a bike close by.” When phase two is over, they are expecting to have 7,000 bike trips a day with the bike sharing program. They will then use the data from the bikes GPS to keep improving the routes. “By examining the routes people are taking”, he claimed, “we will protect the most used tracks and add new tracks where people most need them.” This is exactly as Copenhagen does on their routes. The government does not want to waste unnecessary money on routes people are not going to use. By examining how people are actually using the routes, they can spend resources in a more logical way.

Just as Jane Jacobs, Morataya is trying to become a “student of cities” when it comes to improving the transportation in Guatemala City. We discussed briefly the strategies they want to implement when it comes to phase three of the biking routes. He explained how they will analyze extensively the results of phase two to determine what needs to be done on the next stage. They do, however, have some notion of phase three. The Department of Urban Mobility wants to double the tracks for phase three for a total of “roughly 110 kilometers of bike lanes,” on the condition that phase two is a success. This expansion area would be more complicated as the streets are not as flat; The team is considering the use of electric bikes to solve this issue.

Morataya and I continued with the interview and throughout it, especially at the end, he constantly repeated the importance of public transportation for the project to work. He stated that “all bike sharing stations need to be close to bus stations. We are not expecting people to commute merely on bikes but rather, use the bikes to facilitate the bus travel. The bike’s goal is to solve the last mile problem.” He also mentioned the planned “Aero Metro”, a proposed cable railway that will connect the outskirts of the city to the main axial road. This project has yet to start construction, nonetheless, Morataya is already planning bike routes to connect to the proposed stations.

Morataya concluded by expressing why he believes this whole project will work. “Guatemala City is perfect for biking; it is small, it has a great climate all year long, and traveling by car is less efficient every day. When people start to realize that biking is an efficient and cost-effective way to travel, they will choose not to use cars. Even if 2% of the population star biking, it will make a difference.”

I was also able to talk to Alfredo Maul, the co-founder of BiCuidad. BiCuidad is an activist group working with the city’s government to try to introduce more biking infrastructure and to help provide the citizens with education about it, so it can grow even faster. He explained that the major problem Guatemala is facing right now is that the cycling improvement is only for “recreational uses” and are not a real “transportation option yet.” Maul feels confident the new 2019 plans will improve the current system as they will connect real places and work with public transportation. “BiCuidad studies similar systems on other cities so we can help the government build the best infrastructure. We see the positive effects that biking has brought many cities and we want the same for this country. Once the government realizes that biking could be a real improvement, they will stop creating recreational bike lanes and start creating a real biking infrastructure” (Maul).

If this upcoming development is not plagued with corruption as most developments are, Guatemala can start to see real change. It is too early to know if this change is going to help but at least officials have realized there is a problem. Maybe Guatemala will never reach 62% like Copenhagen but if 2% of the population start biking, it will be a massive improvement.

Conclusion

“The fact is that cars no longer have a place in the big cities of our time.”

No one knows what the future is going to look like. Maybe some other methods of transportation are going to raise, and bikes will no longer be needed. The truth is that cars no longer fit in cities. Cities have to adapt. The world never stops changing and our cities should not either.

As a kid, I thought that future cities were going to be full of flying cars and doubly/triple decking streets. Now, I understand that this is unrealistic. First-world cities should not adapt for more cars but rather, for better transportation systems. The future city I think about today, is a city with incredible public transportation were no one has to be stuck in traffic. A place that can fit millions without any mobility issues. Public transport is a good option but when it combines with cycling, it becomes the perfect option. Biking helps mobility, it is inexpensive, it aids the environment and it helps with the health of its citizens. It is a win-win for everyone in our future cities.

Works Cited

Beaubien, Jason. “The Country With The World's Worst Inequality.” NPR, NPR, 2 Apr. 2018, www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2018/04/02/598864666/the-country-with-the-worlds-worst-inequality-is.

Colville-Andersen, Mikael. Copenhagenize. Island Press, 2018.

“Cycling in the City.” New York City Government, 2018, www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/cycling-in-the-city.pdf.

Dillinger, Jessica. “The Most Dangerous Cities in the World.” World Atlas, 2 Mar. 2016, www.worldatlas.com/articles/most-dangerous-cities-in-the-world.html.

Felipe Q, Oscar. “Uso De Bicicleta En La Usac Gana Aceptación .” Prensa Libre, 25 Sept. 2017, www.prensalibre.com/ciudades/guatemala/ciclovia-usac-alternativa-de-transporte-para-estudiantes.

García, Eddy. “Continúa Proyecto De Ciclovía USAC.” El Sancarlista U, USAC, 10 Oct. 2018, elsancarlistau.com/2018/10/10/continua-proyecto-de-ciclovia-usac/.

Hoffmann, Melody L. Bike Lanes Are White Lanes. University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

“January 2018 Report.” Citi Bike, 2018, d21xlh2maitm24.cloudfront.net/nyc/January-2018-Citi-Bike-Monthly-Report.pdf?mtime=20180216161600.

“June 2013 Report.” Citi Bike , 2013, s3.amazonaws.com/citibike-regunits/pdf/2013_06_June_Citi_Bike_Monthly_Report.pdf.

“June 2018 Report.” Citi Bike , 2018, d21xlh2maitm24.cloudfront.net/nyc/June-2018-Citi-Bike-Monthly-Report.pdf?mtime=20180719165159.

Kont, Jose. “Ciclovía En La Universidad De San Carlos De Guatemala.” ILifebelt, 28 July 2011, ilifebelt.com/ciclovia-de-la-universidad-de-san-carlos-de-guatemala/2011/07/.

Maul, Alfredo. “BiCiudad Interview.” 23 Dec. 2018.

Morataya, Eddy. “Guatemala's Biking Infrastructure Plan Personal Interview.” 21 Dec. 2018.

“Moviendo a Guate.” BiCuidad, www.biciudad.org/uploads/1/1/9/3/11936477/muni_ciclovia_presentacion.pdf.

“9th Avenue On-Street Protected Bike Path.” National Association of City Transportation Officials, nacto.org/case-study/ninth-avenue-complete-street-new-york-city/.

Reid, Carlton. Bike Boom. Island Press, 2017.

Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. “Urbanization.” Our World in Data, Sept. 2018, ourworldindata.org/urbanization.

Russo, Ryan, et al. “Ninth Avenue Bicycle Path and Complete Street.” New York City Government,www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/rr_ite_08_9thave.PDF.

“Why Protected Bike Lanes Are More Valuable than Parking Spaces.” Vox Media, YouTube, 5 Sept. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=E85HMNJix_o.